Taking Strides Toward Reform with Walk Out

September 7, 2018

Ever since the shooting in Parkland, Florida on February 14, it’s been a confusing, heartbreaking, and thought-provoking time for everyone. A month later, on March 14, the Loyola community rallied together in response. Loyola students’ actions on March 14 were a part of the National School Walkout Day, where high schools (and even some middle schools) around the country stood in solidarity with the victims of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

At Loyola, students had the choice to either walk out of class to the football field, pray the rosary in the chapel, or stay in class for 17 minutes. Loyola students showed support for the victims of Parkland and a keen inclination towards political participation, as over 1,300 students left their classes at 10 am on that day, and dozens arrived in room 100B throughout the school day to voice their concerns to lawmakers via phone or email.

The shooting was a shocking wake-up call for Loyola, and had an effect on every student. Before the day of the walkout/chapel movement, a lot of planning had to occur. The National Walkout Movement was brought to Loyola Academy when senior students Lauren Mlynek and Jonas Madison created a “Walkout Facebook page” in late February. Within two days of its genesis, the page accumulated over 400 followers that filled the page with hours of bipartisan political dialogue, wishes for the walkout, and support for the movement overall. This page was responsible for communicating information about the logistics of the walkout, attaching an initial local mission statement for the demonstration, and serving as a medium through which student sentiment was politely shared and discussed.

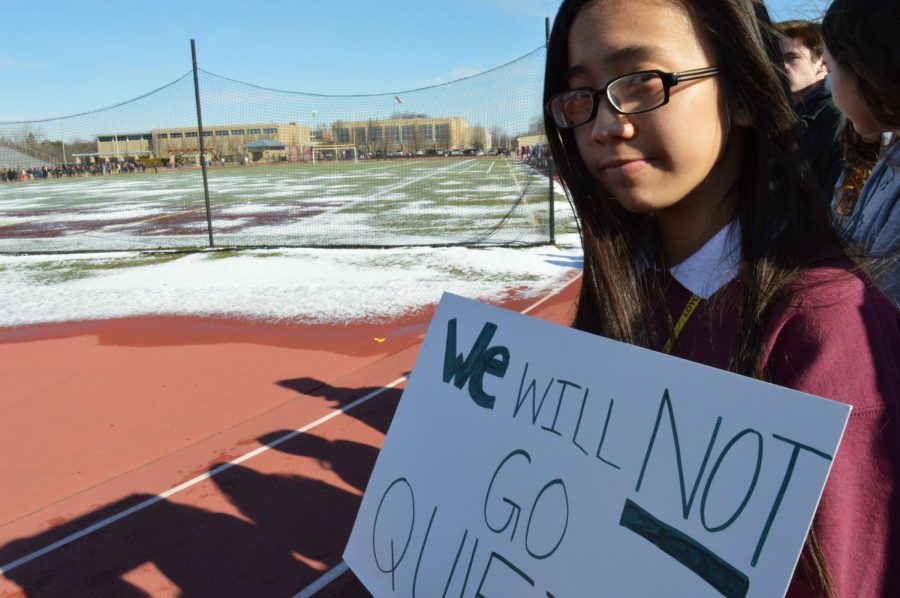

The next week, Dr. Baal, along with various teachers During the March 14 Walkout, students lined the football field to honor the victims and protest gun violence in America. Photo Courtesy Jason Kesse and administrators, invited thirty students, selected for their prominence in leadership positions around the school, to discuss the walkout. It was as a part of this large group that Lauren and Jonas, backed by their social media presence, first got actively involved with administrators in organizing the demonstration on March 14.

Those first two meetings revealed a student body that was deeply passionate about showing support for the victims of the Parkland shooting. The art exhibit hanging in the main lobby, letter writing stations, and the flex-time safety meetings were all created through these initial deliberations.

The thirty student panel was then divided into subcategories to tackle the various aspects of the school’s response: a team of students devoted their efforts to the art demonstrations, another to student outreach and safety, and yet another to organizing the logistics of the walkout itself. It was in these smaller meetings that the students met with Dr. Baal to hash out the physical plan, and to utilize the resources offered by the school.

Out of concerns for student safety, the walkout ultimately convened on the football field – a location that could accommodate the mass number of participants in a space that was secure and local to the school. It was also here that the politics of the walkout were finalized.

Students on Facebook, as well as a profound number of participating students, wished to explicitly associate Loyola’s demonstration with the National Student Walkout movement about gun control, while many others disagreed due to political alignment or a desire to honor the victims first and foremost.

Concern over the school’s public image, as well as the necessity for administrators to remain apolitical, curbed the initial purpose of the walkout to a neutral (but not any less important) message of solidarity and hope. A concession was made, in addition, to the students keen on voicing their political inclinations on March 14.

The original idea was to arm students with contact cards to local lawmakers, and utilize the 17 minute demonstration to call and email them. Dr. Baal specifically wished for “there to be no phones out during the walkout,” so it was later determined to allocate room 100B for students to call policy-makers throughout the day.

Despite the high student participation level, some students had concerns. After the day of the walkout/chapel movement, students were unhappy with the photographer and the email sent to families that separated Loyola’s walkout from the national one.

Senior Jacqueline Topping believed that student options were misrepresented by denying the right to engage politically on the football field.

Senior Jake Brosnan walked out, but believed that the demonstration felt like a fire drill. Both were displeased that the political aspect of the walkout was reduced to one conference room.

Senior Michael Muszynski felt that the seventeen minutes of silence was adequate and the administration was given license to intervene, since students had asked permission to walk out.

Two students not participating in the football field demonstration, Luke Phillips and John Williams, were both staunch in stating that the agenda of the walkout was political, and should have been blatantly recognized as such. Luke Phillips was the student responsible for organizing the chapel service, a decision made by his desire to show support to Parkland in a non-political way, stating: “Loss of life is a human issue, not a political issue.”

He, as well as 300 others, prayed in the chapel to lend non-political support to the voice of the student body. John Williams was an additional participant in the chapel service, who was inspired by the political activism in his fellow students, but also believed that the football field demonstration was turned into something it was not by the administration.

Despite common grumblings about a loss of autonomy, the students of Loyola Academy, whether participants or not, demonstrated a moving political and social dialogue to an extent never previously seen at the school. After the walkout/ prayer in the chapel, The Prep sent out a survey, and around a hundred students from all grades responded. A good number of the responses to the final question, “What message would you like to send to the Loyola community regarding the walkout?” demonstrated confusion towards the purpose of the walkout and/ or unfounded beliefs about administrative decisions.

Despite common grumblings about a loss of autonomy, the students of Loyola Academy, whether participants or not, demonstrated a moving political and social dialogue to an extent never previously seen at the school. After the walkout/ prayer in the chapel, The Prep sent out a survey, and around a hundred students from all grades responded. A good number of the responses to the final question, “What message would you like to send to the Loyola community regarding the walkout?” demonstrated confusion towards the purpose of the walkout and/ or unfounded beliefs about administrative decisions.

In an attempt to reconcile this confusion, we sat down with Dr. Baal to get the facts of what decisions were made concerning March 14 and why. The biggest statement she wished to convey was that the walkout movement was in fact student-led and student-driven. From the first time she heard that an idea of a walkout on March 14 was circulating, her mind went to “How do we involve the students?” From the first lunchtime meetings to the final script used on the football field on March 14, students created it all.

Dr. Baal noted that her only positions were to facilitate conversation between students, print orange name tags for the students and faculty walking out, and, above all, make certain that students would be safe.

When asked what she, as principal and voice for our school, wanted the message of March 14 to be, she responded: “I wanted it to be about the human dignity of life and the 17 lives that were lost due to gun violence. I wanted it to be about the lives that are lost on the West Side of Chicago: we have students here who have family members who’ve been killed by gang violence; that’s what the walkout stood for. How do we pray for the souls of both the people who are dead and pray for the souls of people who feel that their only way in life is to use gun violence? You have to pray on all levels, you know? You need to pray for people who are mentally ill, you need to pray for the doctors who work with the mentally ill. . . It’s about a lot of those things, so I think in those 17 minutes it was a tribute and a memorial to those victims and to other victims who’ve been killed by gun violence, especially in a city like Chicago.”

Dr. Baal acknowledges that there were students whose ideas for the day weren’t implemented, from walking out to the quad (where there wouldn’t be access to a speaker system), to having students call legislators during the walkout.

To specifically address the idea of calling legislators, she wanted to make it clear that if gun reform is what they really, truly stood for, that “those 17 minutes should become 17 days, 17 weeks, 17 months” dedicated to the political cause. She states: “That’s what ‘committed to doing justice’ is, that’s what grad-at-grad is. It’s not doing it once for 17 minutes to make a stand, it’s being committed to making a change.”

Ultimately, Dr. Baal encourages students to make sure they have the information before making a judgment, to be aware of how much planning and thought had to go into the walkout, to clearly see that safety was the priority, and to understand how the administration had little influence in the student-led movement.

Now, two months after the Parkland shooting, excitement over the #NeverAgain movement has diminished despite numerous occurrences of guns going off in schools, and being used in violent crimes. This issue still plagues America’s schools and communities. T

he walkout scheduled for April 20 to commemorate the victims of the Columbine mass shooting is another outlet through which students can continue their cause towards preventing violence inflicted by guns. While governmental resistance is evident – with Governor Bruce Rauner recently vetoing an Illinois bill calling for increased gun license prices – students are banding together in marches, organizing teach-ins regarding policy, and walking out to show that they will not back down from the challenges.